Room II

The discovery and the excavations

"citra Placentiam in collibus oppidum est

Veleiatium"

on the hills at South of Piacenza there is the town of Veleia and his

citizens

(Plinio, Nat. Hist. VII 163)

The existence of the roman city of Veleia has been certified by ancient

sources but any further information, including the area where it was built, had

been lost soon. In 1747 the dean of the Macinesso Parish Church found the

fragments of a bronze inscription and, unaware of its great value, sold them to

the nearby foundries. Fortunately, it had not been destroyed thanks to a scholar

(of that period) that recognised its artistic value and, together with Antonio

Costa, canon of/in the Cathedral of Piacenza, bought the missing fragments.

Two years later, two scholars, Ludovico Muratori and Scipione Maffei, identified

the Tabula Alimentaria traianea , the institution established by Nerva and

developed/pushed ahead by his successor, Trajan.

Muratori also realized that the place where they had found the inscription was

the site of the ancient Veleia.

After this remarkable discovery, the Duke of Parma don Filippo I di Borbone,

aiming at competing with his brother, the Duke Carlo III, that was exploring at

that time the roman site of Pompeii, officially started the excavations and, a

few months later, founded/established the Ducal Museum of Antiquities, now the

National Archaeological Museum of Parma, in order to receive the findings.

A view of the Archaeological Excavations of the Roman town of Veleia

From 1760 to 1765 almost the whole of the ruins of Veleia were unearthed: in

1760 the excavations unveiled the forum and the surrounding portico; in 1761 the

basilica disclosed twelve marble statues portraying members of the Julio-Claudian

Family; then, the excavations reached the upper terraces, that revealed the

thermal centre and the surrounding houses.

The excavations in Veleia came to a first stop with the death of the Duke, and

started again in 1800, first with the Duchess Maria Luigia, then under the

control of the directors of the Museum. In 1876 Giovanni Mariotti found the

ligurian necropolis with the cinerary urns in the north-east area of the roman

settlement.

The efforts of the following directors were focused above all on the restoration

works of the buildings. During the last research, in the 1960s, the employment

of new scientific methods allowed the chronologic distinction of the different

building phases and the correct interpretation of some buildings, such as the

castellum acquae ( the water tank or reservoir ) that, correctly recognized in

1763, was then misinterpreted as the amphitheatre and as such restored at the

beginning of the XIX century.

The history

The Roman city of Veleia was founded after the defeat in 158 BC of the

Ligures Veleiates who fought against the Roman expansion, with the aim of

controlling and managing a huge mountain area between the Taro and the Trebbia

Valleys. The most ancient burials, which were discovered there in 1876, belonged

to a pre-existing local settlement.

Shortly after the first half of the I century BC it became a Roman municipality,

acquiring the right of citizenship, and witnessed a season of development with

the construction of monuments and buildings: the marble statues of the Julio-Claudian

cycle discovered in the basilica and the huge number of monuments are evidence

of the important relations held with the imperial family. But this state of

prosperity did not last long: in the first half of the II century AD the

concession of the Alimenta, the Institution founded by Trajan, showed the

interest afforded by the central authority to the economic crisis of the city,

where the landed property was under the control of a few rich landowners and

many lands were taken up by woodlands or used for pasture, with the obvious

consequence that there was a large number of poor people among the small

landowners.

The study of toponymic and onomastic data clearly shows that Veleia was a Roman

city in a never completely Romanized context: besides the Latin names, we can

find names and surnames of Ligurian origin, such as Ligurinus and Ligus, as well

as Celtic elements, such as Noviodunos ( from the Celtic novio = new and dunos =

fortress).

From the III century AD on the crisis is clear: life in the city is witnessed

until the V century AD at least. The end of Veleia can be placed in the general

trend of depopulation of that time, after the fall of the Western Roman Empire,

when a lot of Italian cities were abandoned.

A parish church devoted to Saint-Anthony ( the “Pieve di Sant’Antonino”) has

been erected on the area of the ancient Veleia, now completely buried.

The Roman city

Veleia looks like a typical mountain centre, with its buildings placed on a

terraced hillside, partly natural and partly artificial, and the structures for

the religious, social and civil life (the latter belonging to the most powerful

families) organized around the forum.

The forum of Veleia was formed by a square, paved by slabs of sandstone, closed

on one side by the basilica, where justice was administered and public functions

carried out; it was surrounded on the other three sides by a portico, with the

tabernae (the shops). In the main room of the basilica, statues of marble from

Luni, portraying the members of the Julio-Claudian family, were aligned on a

podium against the back wall.

In the second half of the I century AD, on the northern side, facing the

basilica, a monumental entrance with columns on two sides was placed to connect

the inner portico with a new one, probably planned for public use.

On the upper terrace, overlooking the basilica, there are the ruins of the bath

(thermal spa), belonging to the Imperial period, and the built-up southern

district, including the Domus del cinghiale, a clear example of a Roman house

with atrium.

The present appearance dates back to the Imperial period but traces of more

ancient times have been unearthed in different areas of the town.

Ruins of the bath (thermal spa) - Archaeological site of Veleia

The bronze items

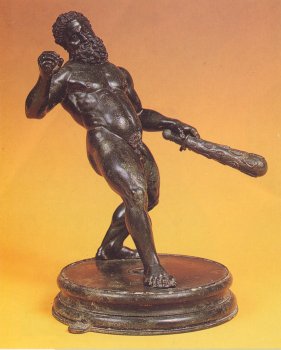

The bronze items, produced mostly by workshops in the North of Italy, are artefacts of a high quality. Among these, the most remarkable are a head of girl (end I century BC), a head of emperor (room 4), probably the portrait of Antoninus Pius (138-161 AD), a winged Victory (I century AD), certainly part of a commemorative monument, and a votive statuette representing a drunken Hercules (II century AD).

Left: Winged Victory (I century AD) - Right: Drunken Hercules (II century AD)

Room III

The Julio-Claudian cycle of marble statues

The twelve statues of marble from Luni, portraying the members of the Julio-Claudian

family, were aligned on the podium of the basilica for clearly commemorative

purposes and represent today the political propaganda of the imperial family in

the North of Italy. They probably all had dedication plaques, but only five of

them still survive. In the case of Veleia, the link with the imperial court is

represented by L. Calpurnio Pisone, patron of the city and Julius Caesar’s

brother-in-law.

The religious significance attached to the cult of the imperial family is

witnessed by the high number of togaed figures and statues with veiled heads (in

latin, “velato capite” statues).

The cycle seems to have been realized at different moments: the first group,

under Tiberius’s rule, consisting of Tiberius himself (headless), Augustus and

Livia (Tiberius’s mother), the two Drusi, Major and Minor (brother and son of

the Emperor) and the realistic portrait of Lucio Calpurnio Pisone Pontifex, who

most probably commissioned them. The statue of L. Calpurnio Pisone follows the

classical representation of the pontifex with veiled head, modelled on the

portrait of Via Labicana, Rome. The identification of two headless statues with

the figures of Augustus and Livia was possible thanks to their corresponding

dedicatory plaques.

Marble statues of the

Julius-Claudian cycle from the Basilica of Veleia

The second group was formed by Caligula, whose head had been replaced after his

damnation memoria, that is the condemnation of the figure depicted, his sister

Drusilla and his mother Agrippina Major.

In the third group there is the statue of Claudius, whose head replaces

Caligula’s, together with his last wife, Agrippina Minor, and her little son,

Nero.

Finally, a loricate statue, whose identification with Domitian or Germanicus is

still controversial among scholars. In any case its head was used again

afterwards, probably in honour of Nerva.

Room IV

The Tabula Alimentaria

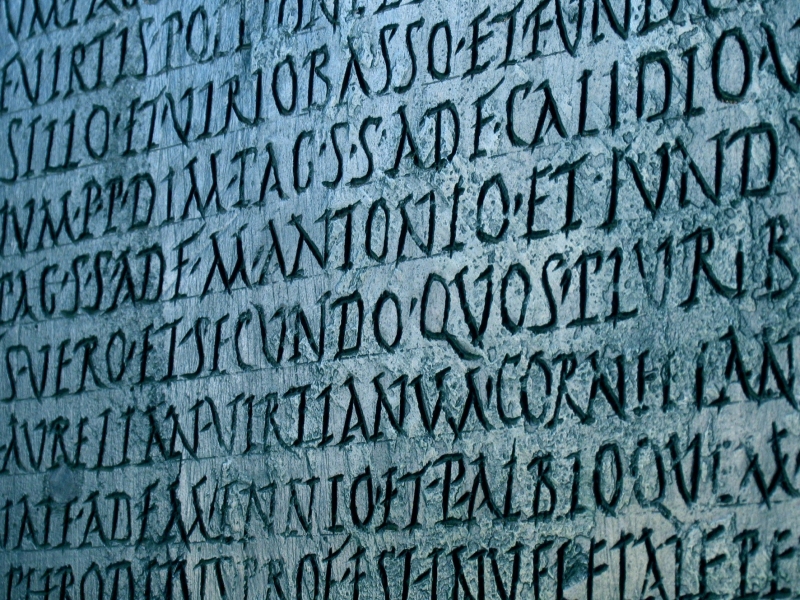

This wide inscribed bronze table (m 1,38 x 2,86), found in 1747 in the site

of Veleia, represents a document of great value since it witnesses the

institution for the city of the alimenta, a mortgage loan granted by the Emperor

to the landowners of that area, and whose interest was allocated for the

maintenance of poor children. It was a great financial action established by the

Emperor Nerva (96-98 AD) and developed by his successor, Trajan, in order to

support young people who could guarantee to the Empire future generations of

soldiers and officials of Italic origin. The emperor’s main purpose was to

prevent the fall in population and the economic decline of Italy at the

beginning of the II century AD. The Tabula Alimentaria showed the Emperor’s

instructions (ex indulgentia optimi maximique principis) for the institution of

a indefinite mortgage loan on lands (obligation praedorium), directly paid out

from his private coffers (fiscus). The loan was divided into two consecutive

disbursements in sestertii and the interests, at a rate of 5% per year, were

allocated in sestertii or in kind (wheat) to 245 legitimate sons and 34

legitimate daughters, plus an illegitimate son and a daughter. This grant

corresponded to the essential minimum sum a person could survive on.

The loan was granted to Veleia and to some neighbouring cities, such as

Piacenza, Parma, Libarna and Lucca, in proportion to their landed properties.

The landowners were listed in more than six columns, indicating their names, the

name of the intermediaries, the estimation of the properties (eastimatio) and

the sum of money paid out. Then, the name of the land (vocabulum) and of two

neighbouring lands at least, its use, its structures (farmhouses, sheepfolds and

furnaces), and its location in the district (pagus) or in a village (vicus).

This inscription offers undoubtedly a cross-section of the condition of the

Apennines near Piacenza at the beginning of the II century AD, revealing the

gradual building of landed properties, despite the prevalence of pastoral

activities that consequently brought about a limited exploitation of the land,

and the coexistence of the local people together with the Roman citizens,

through the study of toponymic and onomastic data.

The Tabula Alimentaria (particular) - Archaeological National Museum of Parma

Public areas

The forum represented the centre for commercial, social, legal and political

activities: besides the essential civil buildings and the surrounding shops, it

also contained the most important commemorative monuments of the city.

The bases of two equestrian statues, dedicated to Claudius (in 42 AD) and

Vespasian (in 71 AD) respectively, are still recognizable, as well as a cippus

of red marble from Verona for the emperors’ worship and the bases of two other

statues, one dedicated to Tranquillina, Gordanius Pius’s wife, and Probus, and

the other to Aurelian (III century AD).

Then, a series of inscriptions, both political and religious, that had to be

manifested publicly, such as the Inscription in honour of Coelio Festo, The

Tabula Alimentaria, and a smaller bronze tablet found in the ruins of the

portico, bearing part of the Lex de Gallia Cisalpina (49 BC), were displayed

there; the Lex is an invaluable text which gives information about Roman civil

procedure and regulates the authority of Roman magistrates who had the faculty

of judging cases not exceeding the value of 15.000 sestertii.

The forum also permitted the display of monuments and inscriptions in honour of

some deserving citizens who had accomplished or renewed public works.

The Veleia's forum

The fragment of wall painting, in third Pompeian style, portraying a garden enclosed with trellises (beginning I century AD) was discovered in the northern area of the portico.

Private areas

Elements of house furniture and crockery, ornamental objects and glassware

found in Veleia, allow us to reconstruct the high level of wealth reached by the

city (showcase 1).

First of all the settlement had a complex network of pipes (fistulae) to supply

water from a huge reservoir (castellum acquae) to the built-up area below.

Windows were closed with wood-framed panels, while a heating system was found in

the bath and in other public buildings.

Both indoors and outdoors, the houses reflected the Roman concept of the living

area as a private and official space, where the expression of power and wealth

was at the basis of the social relationships between the leading classes, the

“patrons” (patroni) and their subordinates, the “clients” (clientes). It was

precisely in these official rooms that mosaic floors and fine furnishings, such

as bronze oil-lamps, used single or like candelabra, were more often employed.

Terracotta oil-lamps were used by common people for everyday life.

The high-quality bronze material discovered in Veleia was not manufactured in

this area; for instance, the female bust within circular clypeus, the sconce

with the warrior bust, and the furniture base with the warrior in combat, were

Cisalpine productions; the pelike, a bronze jug, damascened with silver ( I

century BC) was a Southern Italian production, and the sconces with bust of

Silenus and juvenile bust, supports of a triclinium bed, came from the eastern

Mediterranean.

The comfort of everyday life is certified by the large number of objects used

for body care (showcase 2): glass unguentary vases and balsamaria (balm vases),

strigils, used to wipe sweat and dust off after gymnastic exercises or to remove

oils and unguents after bathing; spatulae, tweezers, beauty products and

toiletries. Then, fibulae, rings and pins represented the essential ornaments

for clothes and hair.

In every Roman house, whether rich or humble, small altars (larari) were devoted

to the worship of ancestors or household gods, the lares. A small statue,

portraying a veiled head offerer (first half of the I century AD), represents

the transposition of the official religion and the emperors’ cult in a domestic

location. In the middle of imperial age, the diffusion of the cult of Isis, the

Egyptian divinity, frequently identified with the Goddess Fortuna, reached its

peak throughout the Roman world.

Precious glass cup (patera) (end of I century B.C.- beginnings of I century

A.D.)