Banca Malatestiana

Palazzo Ghetti

Via XX Settembre 63

Rimini (Italy)

Info and free tour

tel. 0541315811 -

info@bancamalatestiana.it

We

chose this building as our bank’s ideal head office due to its deep-rooted links

with the history and collective imagination of this city and also with the aim

of saving from disrepair the fascinating former match factory owned by Cavalier

Ghetti. We commissioned meticulous scientific restoration work on it so it would

return to how it looked almost two hundred years ago. Beyond even our greatest

expectations, excavations in the building’s courtyard revealed a wealth of

archaeological artefacts, dating from various centuries of history. We now wish

to share with those who are excited to see what was brought to light this small,

but to us very dear, museum open to the entire city.

We

chose this building as our bank’s ideal head office due to its deep-rooted links

with the history and collective imagination of this city and also with the aim

of saving from disrepair the fascinating former match factory owned by Cavalier

Ghetti. We commissioned meticulous scientific restoration work on it so it would

return to how it looked almost two hundred years ago. Beyond even our greatest

expectations, excavations in the building’s courtyard revealed a wealth of

archaeological artefacts, dating from various centuries of history. We now wish

to share with those who are excited to see what was brought to light this small,

but to us very dear, museum open to the entire city.

Banca Malatestiana President, Enrica Cavalli

The archaeological excavations conducted during the restoration of the

Palazzo Ghetti in Rimini, made possible by the collaboration between the

Archaeological Superintendence of Emilia-Romagna and Banca Malatestiana, have

allowed important evidence to be recovered, concerning not only the history of

human activities in this area, from the Roman era through to the present day,

but also the changes that the land itself has undergone during this long period

of time. The significance of the information gathered, the results of which are

presented here preliminarily, the interesting features of some of the structures

revealed and the objects found during the excavations made it necessary to

identify the most appropriate way to present these discoveries, making them

accessible to the public. The proposal of an exhibition space in the building

restored to house the head offices of Banca Malatestiana was therefore received

favourably by the superintendence, believing this option to be a further step in

the safeguarding and enhancement of our cultural heritage that started with the

archaeological excavations and now continues with this display project. It is

therefore particularly important, at this present moment in history, to be able

to recognize this initiative as an example of the promotion of the cultural

heritage, and in particular of the archaeological treasures that form such an

important part of our story.

Soprintendente per i Beni Archeologici dell’Emilia-Romagna, Filippo Maria

Gambari

Display itinerary

Notes on the history

Around the Italian Unity (1861), between the few industries of Rimini

there was the Nicola Ghetti’s match factory, that in 1866 has more than 350

workers, mostly women.

Established in 1837 in a different location, it was definitively fixed in 1857

in this building, that includes the factory and Ghetti’s mansion. It had been

designed by architect Giovanni Benedettini, who worked together with architect

Poletti at the realization of Galli Theatre in Cavour Square and designed other

important buildings in town.

In origin the residential wing was surmounted by an attic with a terrace toward

XX Settembre Street; on the attic there was an octagonal turret with two clocks

and a lantern on the top. The match factory was considered all along the

nineteenth century a very advanced building, because of its sanitary equipments,

but once dead Nicola Ghetti, went in crisis with the depression of the late

nineteenth century, was sold in 1896 and gave up the activity in 1908. The

mansion, collapsed the turret with the earthquake of 1875 and the turret with

the one of 1916, in the Twenties lost both the attic and the terrace and was

covered with the actual roof. Even the three wings of the factory lost their top

floor.

The whole building was sold and converted to residential use, divided in flats,

with stores and workshops at the ground level.

The building fell into decline till 2000, when the Municipality of Rimini,

become owner of it, restored the only residential wing, in order to turn it into

offices. In 2005 Banca Malatestiana bought by auction the building and started

an integral restoration to realise its new headquarter, according the project by

Cumo Mori Roversi Architects, ended in 2013.

The restoration (2007-2013)

The aims of the project were the realization of Banca Malatestiana new

headquarter and the recovery of the urban value of the building, with the inner

route. The building, that was in a state of utter neglect, showed itself as the

result of joining of different parts. The residential wing, even if recently

renovated, did not show appearing traces of its original decoration any more,

but the two painted ceilings at the ground level. Also the external walls looked

very different from the original aspect. By a special study on the plasters it

has been possible to find out and reproduce the original finishing and colours

of the external walls; the paintings on the intrados of the main stairway have

been discovered and restored. Almost all the technical devices and implants have

been concentrated into new dedicated spaces in the underground of the big

rectangular court, in order to preserve the ancient rooms.

The most important implication of the realization of the new underground has

been the archaeological excavation that interested the whole court and the

outdoor rear area, under the direction of the Archaeological Superintendence.

The project , approved by the Architectonical Superintendence, aimed at

recovering the internal spaces, by introducing a new system of partitions, that

did not reach the ceilings and the roof, keeping them in complete evidence.

Archaeological

excavations

Archaeological

excavations

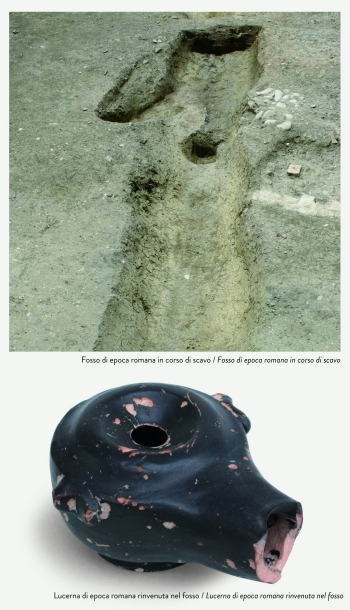

Excavations carried out in two courtyards areas of the Palazzo Ghetti in

2009 and 2010, under the supervision of the Archaeological Superintendence of

Emilia-Romagna, revealed traces related to the production activities of the

18th-century match factory. At the depth of one metre, a number of mediaeval

structures of the old San Genesio quarter, now San Giovanni, were discovered.

Houses, shops and storerooms opening onto a street and courtyards with waste

tips containing a wealth of materials gave an interesting view of daily life in

Rimini in the 14th and 15th centuries, when it was ruled by the Malatesta

dynasty. The old quarter was built over a cemetery dating back to the Roman

Imperial period, situated as was customary along a main road outside the town,

and in this case the ancient Via Flaminia, now Via XX Settembre, which started

from the Augustus Arch and led to Rome. Finally, beneath the remains of crop

cultivations, drainage trenches dug by the Romans from the middle of the 3rd

century BC onwards to reclaim the local marshland were found. The ditches were

subsequently filled in with soil and refuse, which yielded several pieces of

pottery and other important items for the history of Rimini.

FROM ROMAN ERA TO LATE ANTIQUITY

The origins of the Quarter

After founding the colony of Ariminum in 268 BC, the Romans started to

reclaim and divide the surrounding land using the method of centuriation,

consisting in a grid of roads and drainage channels oriented towards the main

cardinal points, or following the slope of the land or the presence of

watercourses. The ditch found in the excavation of the main courtyard of the

Palazzo Ghetti dates back to this period, running from north to south, parallel

to the “Cardo Maximus” of the city, the present-day Via Garibaldi and Via IV

Novembre. Towards the south, the ditch became wider and deeper, perhaps to allow

it to collect water better. It remained in use until at least the 1st century

BC, and was filled in with soil mixed with numerous fragments of black-gloss

pottery mainly from the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, but in some cases probably

from the 4th century, including plates, lamps and jars, some with engraved

letters. Numerous sections of flooring slabs were also found, perhaps from

masonry water tubs. Spacers from pottery firing and large blocks of burnt

fireclay found in the ditch filling suggest that there was probably a pottery

kiln nearby. Two artefacts in terracotta are of particular interest, one a small

domestic ceramic altar painted with the image of an ox, and the other an antefix

showing a winged female figure. Several coins, fragments of amphorae, bricks and

metal objects were also found together with these materials, including a Roman

fibula that seems to have been modelled on Celtic designs.

The filled-in ditch was perhaps replaced by or linked to smaller channels

probably associated with the cultivation of the fields

The

Necropolis and the well

The

Necropolis and the well

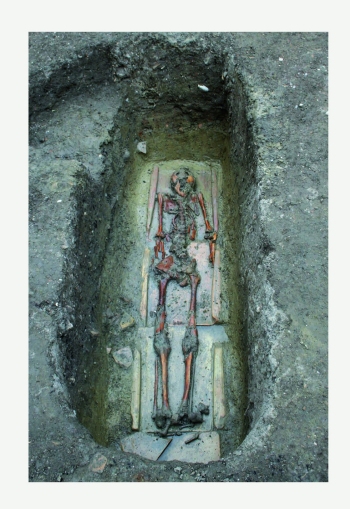

Between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD the level of the countryside gradually

rose, and a number of small furrows and residues of fires suggest activities

linked with agriculture.

Later, in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, the area was marginally occupied by a

series of burials, probably on the edge of the necropolis that developed

alongside the Via Flaminia, characterized in many cases by monumental burials.

The tombs found during the excavations were more modest, with a burial chamber

made from roofing tiles, inside which the body was laid for interment.

During the excavations a well was also discovered, perhaps originally lined with

cobblestones. The filling of soil mixed with masonry yielded the neck of an

amphora and an intact jug.

The area probably continued to be used as a burial site up to the 5th or 6th

century AD, as indicated by a number of coins found in some graves.

An interesting hypothesis, which still however remains to be proven, could link

these burials with the nearby Santo Stefano Church from the early Middle Ages,

which over the centuries became the present-day San Giovanni Battista Church.

COMMENTARIES

ROMAN CENTURIATION IN EMILIA

When a new territory was occupied, it was common practice during the

Roman Republican and Proto- Imperial periods to allocate the lands to settlers.

These areas underwent centuriation, in other words they were divided into

regular, square sections called centuries, which were square and had straight

roads and right-angle junctions, from which single plots of land were obtained.

The procedure was standardized and was carried out by specialists using tools

that permitted the exact identification of the cardinal points or “grome”. In

Emilia centuriation was carried out in various periods.

The oldest of these, in the area of Rimini and Cesena, was carried out “secundum

coelum”, in other words its roads were oriented based precisely on the cardinal

points. The remaining territory was oriented “secundum naturam”, which means it

followed the slope of the land towards the River Po and had the route of the Via

Emilia as its base. Each settler was given a plot of land to cultivate on which

they built a dwelling with stable, storehouses and various other production

buildings, such as the “torcularium” or wine press. Some of these dwellings, the

rural villas, boasted an impressive level of architecture with a part decorated

in a variety of different ways for the owner, who was only present occasionally,

and another for the farmer, as well as lodgings for workers.

BLACK GLAZED POTTERY IN RIMINI

The first fine tableware pottery, produced by the kilns of Rimini from

as early as the 3rd century BC, basically immediately prior to the foundation of

Ariminum, was of the type called “black glazed”, which derived from Greek models

of the Hellenistic period. It featured a more or less shiny black coating,

obtained by firing with reduced oxygen in the kiln. Forms were very simple and

the size of the pieces - cups, bowls, saucers and glasses destined to be used

for lunches and banquets - was either small or medium. Only the oldest types

sometimes presented simple painted motifs in white and yellow, which imitated

vegetal decorations typical of Apulian production. Some bowls and cups have also

been found with engraved or painted inscriptions and have been interpreted as

votive items. Pieces with a large H are usually thought to be dedicated to

Heracles. Also fairly common is an imprinted decoration featuring small palm

trees. Typical of the Rimini area is a motif with a multi-petal flower or large

rosette. In the early Imperial period this production was gradually phased out

and replaced by the red glazed variety - so-called “terra sigillata” or “sealed

earth” - with both smooth forms and those decorated in relief.

FIBULAE

Greek and Roman clothes didn’t usually have seams, but instead consisted

in pieces of cloth of differing sizes that were draped in a variety of ways

across the body depending on the fashion dictates of the time. Their stability

was guaranteed by belts and above all “fibulae”, brooches with a sharp needle

and with the upper part, the arch, decorated in a variety of ways. In men’s

clothing, the toga was not supposed to have any fastening elements and the

fibula was primarily used to keep the cloak attached; it was usually positioned

on the right shoulder, with the spring facing downwards.

Women’s clothing on the other hand, envisaged the use of a large number of

fibulae that shaped the neckline and also made it possible to form the sleeves,

which could be more or less closed. Fibulas therefore became ornamental pieces,

veritable jewels that were sometimes made of precious metals and decorated with

reliefs and often enamel inserts such as for example, Gallic fibulae. Fibulae

came in a variety of different styles characteristic of the zones in which they

were produced. This meant it was possible to identify the trade routes they had

followed and to speculate on the provenance of their owners. Military fibulae -

in other words those used by soldiers as part of their uniform or battledress -

were very common and some even bore the symbols of the legions they belonged to.

NECROPOLIS AND BURIAL RITES

Based on a law dating from the period of the Roman Kingdom, tombs in the

Roman period could not be within the city walls. Therefore, cemeteries were

always built outside cities, mainly along roads that were lined with funeral

monuments and pillars; in other words, headstones bearing the names and details

of the deceased. In fact, the Romans believed that in order to maintain the

vitality of the spirit of the deceased it was necessary to commemorate them,

mention their names and carry out specific rites in their memory.

Indeed, they believed that their forefathers protected their families and it was

therefore, a fundamental duty of their descendants to ensure they were

remembered. They even held special celebrations, called “parentalia” with

banquets in the cemetery areas that the spirits of the deceased attended. The

most imposing and oldest tombs were close to the road, whilst those in the

fields, often allocated to confraternities, were the simplest and poorest.

Burials were either by cremation or inhumation. For the cremation rite the

deceased was burnt on a funeral pyre along with the funeral offerings. The

remaining bones were collected and placed in a stone or glass ossuary or in a

terracotta urn that were then either buried or stored in the funeral monument.

Inhumation or entombment of the deceased became common during the Imperial

period. The body, which was either placed in a coffin or wrapped in a shroud,

was put to rest in a simple ditch or brick casket which was usually “a

cappuccina”, in other words, it was covered in tiles arranged at an angle.

During the funeral or the funeral rites, libations and offerings were made for

the deceased as it was thought they would be able to use them. In some tombs a

tube, called the “infundibulum”, has been found that led directly to the

skeleton from cemetery level.

DOMESTIC RELIGION: ARULAE AND LARARIA

In all Roman homes of the Republican and early Imperial period there was

a lararium that was dedicated to the Lares and Penates, in other words, the gods

and geniuses who protected the state and the family. In the wardrobe connected

to the lararium, noble families kept portraits of their ancestors. The lararium

was usually positioned in the hall of the house and was shaped like a small

temple on a high podium. Often on the internal wall there were painted

depictions of a god or the Goddess Rome or the god the family worshipped. It

also contained statuettes of the two Lares, dancing and celebrating, the genius

of the Roman people wearing a toga and some favourite gods, often Minerva, Venus

or Bacchus. The statuettes, which were usually bronze but could be made using

other materials, were small and reproduced common typologies. Worship of the

Lares was carried out by the head of the family with daily rites, with libations

and offerings. In front of the lararium there was a small altar on which it was

common to place small offerings of food or flowers or to burn incense or

fragranced oils. In Rimini, several “arulae” have been found; these are small

terracotta altars whose front is decorated in relief with scenes of a religious

or ritual nature, often painted and dating from the Republican period.

KITCHENWARE AND AMPHORAE FROM THE ROMAN PERIOD

Cooking pots and containers in various forms and made using various

materials, depending on their purpose, were used in the Roman period. These

cooking pots were made using clay mixed with other material to make an amalgam

that was heat resistant or at least capable of resisting indirect heat. Large

containers, such as the copper pots that hung above the hearth, were usually

made from metal - copper, bronze or iron - as were the pots and pans, which were

also common in pottery In the latter case however, for cooking the pot or

earthenware jar was hung on a trivet above the embers. General containers, such

as jugs and bowls, were made in pottery and did not have any decorations. To

prepare food a mortar was also fundamental; these were either stone or

terracotta with a base roughened up by other materials. Large containers, such

as dolia, used to store cereals and pulses, were manufactured by specialist

kilns and were often, at least partly buried. One type of large container was

the amphora, a special container used for transporting wine and oil. These were

different depending on the area of production. In the Rimini area the most

common amphorae in the Imperial period had a flat base and were called

“Forlimpopoli type”, named after the town where the kilns were found; they were

used for storing local wine. In the late Imperial period, amphorae of African

production were very popular and were used above all, for wheat and oil. Due to

their considerable size, they were often reused as coffins for burials.

THE MEDIAEVAL PERIOD

The Quarter grows

In the 13th century, the population of this area outside the city

started to increase, as the San Gaudenzo monastery attracted peasants from the

nearby countryside to work its land. By this time, the city authorities had

already erected defences that included wooden palisades, ditches and ramparts,

signs of the economic and social importance that the new quarter was starting to

enjoy. With rule by the Malatesta family in the 14th and 15th centuries, Rimini

flourished both in its economy and its buildings. New inhabitants continued to

arrive from the countryside, settling in the city to work as tradesmen or

shopkeepers, and Rimini’s important road links allowed commerce to prosper. The

San Genesio quarter also grew, with groups of houses outside the walls replacing

the farmland. Historical evidence shows that new brickwork fortifications were

present from as early as the 14th century, when the quarter was closed about 300

metres to the south of the Augustus Arch by the San Genesio Gate, protecting the

Via Flaminia and access to the quarter, and inserted into the old wooden

palisade. In the direction of the city, the San Bartolo Gate was erected, to

protect the bridge over the River Ausa. During the 14th century, with the

constant increase of the population of the quarter and its buildings, often

associated with trades and crafts, work was started on new walls built in brick,

probably terminated around 1450.

The walls were reinforced by towers like that discovered behind the Palazzo

Ghetti, with a polygonal foundation filled with rubble and other materials to

resist against artillery fire.

From excavations to the mediaeval quarter

The archaeological excavations also revealed a road and the remains of

buildings with courtyards and refuse pits from the quarter in the 14th and 15th

centuries. The road, paved with gravel, cobblestones and other materials, led

from the Via Flaminia towards the walls, and was raised and repaired several

times, and probably enlarged around 1450.

A smaller alley wound away from this road between the shops and houses, and

several structures of the San Genesio quarter were discovered alongside it. On

one side there were buildings with the ground floor divided into two areas, one

for business activities as a shop or a tradesman’s workroom, or used for storage

or as a stable, and the other, with a brick hearth for cooking food, for use as

living quarters. Beside the buildings there were small courtyards, sometimes

with ditches for household wastes.

On the opposite side were the partial ruins of a building with more carefully

built walls, suggesting the rear of one of the courtyard houses that had their

entrances directly on a main street, in this case the Via Flaminia. This

building had a waste pit filled with domestic refuse, containing in particular

painted crockery for serving food and drink.

Materials

Various materials recovered during the excavations allow the daily life

of the quarter in the Middle Ages to be more fully understood. The waste pit of

the large courtyard house contained in particular three ceramic objects: a jug

with small floral motifs, used at the table to hold water or wine; a graffito

slipware bowl used to carry food to the table; and finally a small green glazed

pitcher, used to store food or to transport liquids. There were also several

fragments of ceramic cooking pots placed over the fire to prepare soups and

stews. Various pottery fragments attributable to the 14th and 15th centuries

were found on the road, together with a series of metal objects that included

several coins, shedding light both on the trade activities of the quarter and

the origin of travellers. Some of the objects came from the courtyards of the

houses, and in particular a few nails and a sickle, associated with everyday

household activities, for work in vegetable gardens and repairing buildings.

The walls and the Mediaeval tower

The excavations in the outer courtyard revealed a stretch of medieval

walls probably erected in the 14th century and completed in the 15th century by

the ruler of Rimini, Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta. These walls, which probably

replaced an earlier wooden palisade with a moat, protected the former San

Genesio quarter, which had grown outside the main city along the Via Flaminia, a

busy road lined with tradesmen’s shops and taverns. Built in brickwork, the

walls were about one and a half metres thick, and were topped by a parapet and

battlements to protect the defenders. Of the various towers built along the city

walls, the one discovered by the excavations was of particular interest, with a

large polygonal foundation filled internally with rubble to allow it to resist

artillery fire, one of several experiments in military architecture typical of

Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, renowned during the Renaissance for his studies

in the arts of war.

COMMENTARIES

MEDIAEVAL AND RENAISSANCE TABLEWARE

In the early dark ages, the lack of specialist kilns led to the

disappearance of luxury productions, which were limited to only “glazed”

pottery, in other words pottery covered in a thin coating of green or brown

glass, sometimes with relief motifs. This production continued for a

considerable period of time. After the year 1000, “graffita” pottery appeared.

This was covered in a white earth coating, called slip or engobe, on which

decorations were engraved and thus appeared as clay-coloured. These were

subsequently coloured with metallic oxides and covered in the glaze. Only later,

after the 13th century, did majolica appear. First, a vase in “biscuit” - that

is, simple clay fired just once - was made. The vase was then coated in vitreous

white enamel on which decorative motifs were painted. Subsequently, after the

final coating had been applied, the vase was fired a second time to obtain its

characteristics glazed appearance. So-called “archaic pottery” was decorated

with green cooper oxide and black manganese. Later cobalt blue appeared, to

which other colours were added as techniques developed. During the Renaissance

“istoriato-style” pottery became common and was decorated with complex scenes,

often taken from great paintings. In the Rimini area, production came mainly

from Faenza and Urbino. Later white enamel vases with small yellow and blue

images appeared and were known as “compendiario style”.

TYPES OF MEDIAEVAL HOMES

Excluding noble and palatial-style dwellings and veritable castles that

had mainly defensive functions, during the Middle Ages the houses of common

people seemed to have very specific characteristics. It is necessary to

distinguish between simple dwellings and buildings destined for use as workshops

or small stores too. Private homeowners were rare and to all intents and

purposes, should be considered landed gentry, whilst dwellings, which were very

small, were often dependent of monasteries or associations and were rented out

or given in use to employees. They usually consisted in a ground floor with a

hearth and stone or brick walls and a wood first floor that was used as sleeping

quarters; promiscuity was very common. There was almost always a small rear

courtyard, as was common in “courtyard” houses. In Rimini, wall foundations were

made of stone or fragments of brick and were only rarely made using new bricks.

They often had a “trellis-like” structure; in other words a structure with

wooden supports that held up the heterogeneous materials used for construction.

Shop owners and artisans worked on the ground floor, almost always in a single

room that was either common to or separate from the dwelling, often with a large

opening on the façade leading onto the street and with a large brick or wood

sales counter. The flooring on the ground floor was often hard clay with a

hearth of stone or brick, almost always reused. The partitions between the

floors and the stairs were always made of wood, whilst the roof was either wood

or straw, sometimes covered in roof tiles, even ancient ones. Inns and meeting

places in general were larger, with a common room, kitchens, storehouses,

stables and open spaces used for various purposes.

TYPES OF FORTIFICATIONS

Walls and fortifications in general evolved in line with the development

of siege techniques and machinery. The oldest and simplest defences consisted in

a simple rampart with external moat, sometimes with reinforcement elements and

often equipped at the top with wood palisades of varying thicknesses and

heights. The necessary entranceways had lateral protection elements that

developed into towers and mobile bridges for crossing the moat. Defensive

requirements meant that communities had to create walls in more resistant

materials, such as stone or brick, often “rubble masonry”. The walls had to be

fairly thick in order to support a communication walkway at the top and were

generally protected by battlements and had crenels. The great towers, which were

either square or polygonal, were designed to create specific defence points for

positioning machines of war. The invention of fire arms, in particular cannons,

forced changes to defensive systems. Great towers with corners could be damaged

by cannon balls, so mainly circular ones were built with the aim of creating

protections in fire-resistant material and replacing wood elements in order to

avoid the risk of fire as far as possible.

Building the wall that replaced the wooden palisade (14th - 15th century)

Exhibition promoters

BANCA MALATESTIANA

Credito Cooperativo Società Cooperativa

MINISTERO PER I BENI E LE ATTIVITÀ CULTURALI

Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici dell’Emilia-Romagna

Scientific and display project coordination

Renata Curina, Maria Grazia Maioli

Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici dell’Emilia-Romagna

Marcello Cartoceti, Chiara Cesaretti, Luca Mandolesi

adArte di Luca Mandolesi & C. snc – Rimini (RN)

Executive coordination

BANCA MALATESTIANA

Credito Cooperativo Società Cooperativa

Renata Curina, Maria Grazia Maioli

Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici dell’Emilia-Romagna

Marcello Cartoceti, Chiara Cesaretti, Luca Mandolesi

adArte di Luca Mandolesi & C. snc – Rimini (RN)

Scientific coordination for the restoration of archaeological materials

Mauro Ricci

Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici dell’Emilia-Romagna